Individual differences in beat perception affect gait responses to low- and high-groove music

Does our ability to feel the beat affect how we walk when we synchronize our footsteps to music, and what does this mean for patients with different levels of beat perception ability when we use music in gait rehabilitation?

Click here to read the full paper.

Click here to read the full paper.

Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation (RAS) and Parkinson's disease

|

The auditory and motor areas of the brain are highly interconnected with each other. When we hear musical rhythm, the motor system in the brain is active, even when the listener is sitting perfectly still! This is part of the reason scientists are investigating the clinical use of music to treat symptoms of motor disorders, including Parkinson's disease. Patients tend to experience a slower, unsteady walking pattern (gait), which is not always alleviated by medication. There is evidence that listening to a steady metronome beat can help regulate the timing of their gait, and in some studies, the length of their strides increases. The use of this steady metronome beat (or perhaps music that has a steady beat) to help movement is termed 'Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation' (RAS).

|

Where Music Comes In

If people with Parkinson's disease are to incorporate RAS into their daily routine, music may be more motivating to put on than the constant click of a metronome, which by itself isn't a very pleasant or interesting sound to listen to. The complication is that in order to synchronize one's steps with the beat in music, a person needs to be able to perceive that beat of the music easily. The beat is a steady 'pulse' commonly heard in music--it is what you'd tap your foot or clap your hands to. We know from previous studies that the ability to perceive the beat varies dramatically across the population: some are excellent at feeling the beat, and others are terrible.

Moreover, studies of patients with Parkinson's disease have found that patients perform worse than non-patients on beat-based rhythm tests. So, it might be that whether one's walking is improved by synchronizing to music depends on your ability to feel the beat.

One solution could be the clinical selection of music that is high in groove, namely, music with a clear beat, and that listeners have said makes them 'want to move'. To determine whether high-groove music could eventually be helpful to patients, the current study first tested the effects of high and low groove music on a neurotypical adult population that varied in the ability to feel the beat.

Moreover, studies of patients with Parkinson's disease have found that patients perform worse than non-patients on beat-based rhythm tests. So, it might be that whether one's walking is improved by synchronizing to music depends on your ability to feel the beat.

One solution could be the clinical selection of music that is high in groove, namely, music with a clear beat, and that listeners have said makes them 'want to move'. To determine whether high-groove music could eventually be helpful to patients, the current study first tested the effects of high and low groove music on a neurotypical adult population that varied in the ability to feel the beat.

Predictions

|

Bruno Mars, James Brown, Maroon 5, and Esperanza Spalding are just a few artists known for their high-groove music.

|

We tested people's beat perception ability with the Beat Alignment Test (BAT). We then asked people to synchronize their footsteps to music while we measured several parameters of their gait:

We predicted that people who did well on the BAT, or 'strong beat-perceivers', wouldn't have trouble with synchronizing to high-groove music, but that 'weak beat-perceivers' would. This is not only because it's harder for weak beat-perceivers to sense the beat, but because the extra attention required to try to find the beat would create a second task that would slow them down (much like how other attention-demanding tasks, like talking on the phone, slow our walking pace). In both strong- and weak beat-perceivers, low-groove music would elicit slower and more cautious gait than high-groove music. Metronomes have a strongly felt and readily discerned beat, but they typically don't cause emotional responses; therefore, metronomes are a good control when evaluating whether gait changes in the high-groove condition are due to a clear beat (as present in the metronome itself) or other, music-specific, factors. |

Methods

- Forty-three healthy undergraduate students from the University of Western Ontario participated.

- Prior to starting the step synchronization task, each participant rated 20 pre-selected music clips on groove, familiarity, and enjoyment on a 10-point scale. Based on individual ratings, the three music clips lowest in groove and the three music clips highest in groove were selected for each participant. To reduce the likelihood that familiarity with the music clip would confound the results, only low familiarity clips were used.

- After walking in silence to determine a baseline cadence (normal walking rate), participants walked during each of the following 'cue' conditions: low-groove music, high-groove music, and metronome sequences. They walked to music (1) adjusted to their normal walking cadence and (2) at a 22.5% faster than normal.

Results

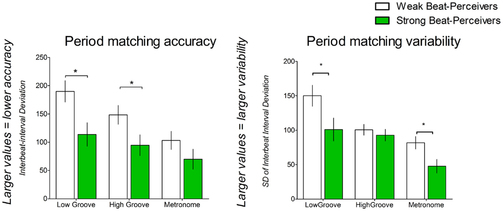

Low-groove music was hard to synchronize to. Participants' ability to match the rate of their footsteps to the rate of the music (called 'period matching' in the graph) was poorest with low-groove music, intermediate with high groove music, and best with the metronome.

Low-groove music also elicited larger and more variable deviations.

Weak beat-perceivers (shown in white bars) were worse at synchronizing than strong beat-perceivers (shown in green bars).

Low-groove music also elicited larger and more variable deviations.

Weak beat-perceivers (shown in white bars) were worse at synchronizing than strong beat-perceivers (shown in green bars).

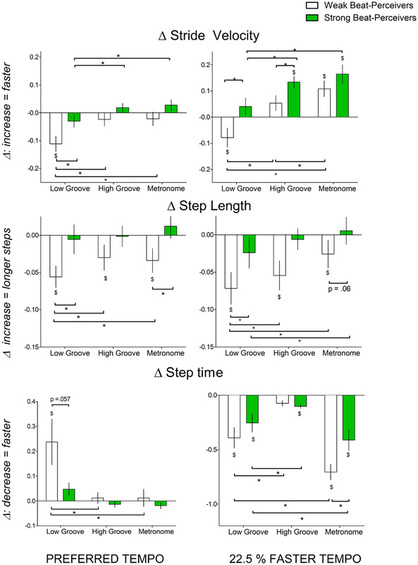

Low-groove music was also bad for gait, as it elicited slower and shorter steps compared to uncued walking. High-groove music and metronome cues had similar effects on speed and step length, suggesting that high-groove music might be just as good as metronome cues in altering gait parameters.

Weak beat-perceivers (shown in white bars) showed overall slower and shorter steps than strong beat-perceivers when synchronizing to auditory cues. These effects were particularly evident with low-groove music, which reduced step length at both normal and faster tempos in weak beat-perceivers.

The shorter and slower steps in weak beat-perceivers might be because synchronizing movements to auditory cues is attention-demanding for them. The negative effects of synchronization on gait parameters were evident even with metronome cues, when there was no need to extract the beat from the music.

Under all cueing conditions, step length did not significantly increase compared to normal baseline walking. Participants moved faster, but by taking more frequent (decreasing step time), not by taking longer steps. These findings are important because the slowing of gait in PD results primarily from steps that are too short, thus simply presenting faster cues may not help increase step length.

Summary

- Weak beat-perceivers' gait was worsened by synchronizing to music: they showed larger increases in stride width and stride length variability than strong beat-perceivers, and this pattern of results was particularly evident with low-groove music.

- Difficulty in perceiving the beat could limit the beneficial effects of music on patients' gait if they are required to synchronize footsteps to the beat. Weaker beat perception in patients might further increase the attentional demand of synchronizing footsteps to the beat, thereby worsening gait in patients with PD, as they generally show weaker attentional control than healthy individuals when walking.

- These findings suggest that asking individuals who are weak beat-perceivers to synchronize to metronomes or music might actually make their gait worse. Tailoring auditory cues according to an individual's beat perception ability might elicit better outcomes in gait rehabilitation.